We speak endlessly about unexpected discoveries, unexpected encounters, and unexpected insights. That alone should make us pause.

If something is described as unexpected simply because we did not know what to expect, then ignorance suddenly becomes a virtue — and expertise a disadvantage. That cannot be right.

To understand why this matters for serendipity, we need to disentangle three concepts that are too often used interchangeably: unexpected, surprise, and unanticipated. They are not the same. Confusing them has quietly distorted how serendipity is understood.

Unexpectedness: a weak epistemic category

At its core, unexpectedness says very little about the world — and a great deal about the observer.

Unexpectedness depends on the observer’s ignorance, lack of preparation, or limited frame of reference.

What is unexpected to a novice may be obvious to an expert. For a child, the world is full of unexpectedness; for an adult, far less so. A tourist experiences endless surprises; a local sees familiar patterns.

Unexpectedness is therefore natural for a newcomer and scales with ignorance. The less one knows, the more unexpected the world appears. As a concept, this makes unexpectedness a poor foundation for understanding discovery or insight — and when used to define serendipity, it becomes actively misleading.

Unexpectedness tells us that something fell outside an expectation — but not whether that expectation was well founded, theoretically informed, or simply absent.

Surprise: an emotional response, not an explanation

Surprise is something else again.

Surprise is not a cognitive category but an affective reaction — the feeling of being caught off guard. One can be surprised by trivial novelty, by noise, by deliberate manipulation, or by carefully staged experiences. Surprise can be engineered. It can be simulated. It can be sold. Advertising has perfected this logic. By engineering surprise and novelty, it directs attention toward what is salient rather than what is relevant — training us to react rather than to think.

Surprise may accompany insight, but it does not guarantee it. One can be surprised without understanding anything at all.

For this reason, surprise cannot serve as a defining feature of serendipity. At best, it is incidental. At worst, it distracts attention from the real work of interpretation and sensemaking.

Why serendipity cannot rest on the unexpected

Since my weekend visit to Pek van Andel’s house (2015) I have wondered, why unexpected is a cornerstone of the definition for serendipity! And even more I have wondered why no one in serendipity research has ever questioned it – it is the dilemma of “Walpolean serendipity”.

If serendipity were primarily about the unexpected or the surprising, then those with the least knowledge would be its greatest beneficiaries. History shows the opposite.

Serendipitous discoveries tend to occur within domains of expertise, not outside them. They arise in contexts where expectations are already disciplined, theories are in place, and patterns are actively anticipated.

This brings us to the concept that actually matters.

Unanticipated: the serendipity-specific concept

Unlike unexpected, unanticipated does not refer to ignorance. It refers to the limits of even expert anticipation.

An expert anticipates many things:

- regularities

- anomalies

- failure modes

- plausible outcomes

What defines the unanticipated is not that no one could have expected it, but that it escaped anticipation within the existing theoretical or conceptual framework.

This distinction is crucial.

The unexpected flatters ignorance. The unanticipated challenges expertise.

And it is precisely here — at the boundary of expert understanding — that serendipity becomes possible.

Anomaly, not surprise: what the classics actually say

This brings us to an important and rarely acknowledged point.

In both Robert K. Merton’s serendipity pattern and Pek van Andel’s anatomy of the unsought finding, the core element is not surprise or mere unexpectedness, but unanticipated significance — often first encountered as an anomaly.

Both Merton and van Andel repeatedly use the term anomaly to describe the initial trigger of serendipitous discovery. An anomaly is not a feeling. It is not an emotional reaction. It is a cognitive and theoretical disturbance: something that does not fit existing expectations, models, or explanations.

By contrast, much contemporary serendipity discourse casually replaces anomaly with surprise. This substitution may appear harmless, but it is not. It shifts attention away from theory, interpretation, and understanding — and toward momentary affect.

This shift in vocabulary signals a deeper conceptual drift: from serendipity as a process of sensemaking triggered by anomalous observations, to serendipity as a subjective experience of being surprised.

In making this shift, the very essence of serendipity is quietly altered.

Why this distinction matters

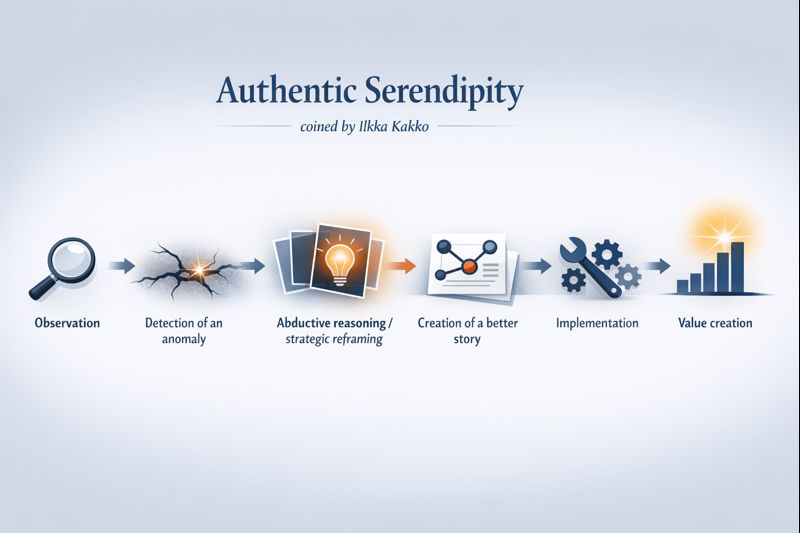

Serendipity does not emerge from being surprised, nor from encountering the unexpected. It emerges when an unanticipated anomaly is recognized, interpreted, and pursued by a prepared mind — and only later validated through effort, implementation, and outcomes.

If contemporary definitions of serendipity are taken at face value, “Walpolean serendipity” would imply that ignorance is an advantage: the less you know, the more serendipitous your world becomes. That cannot be right.

This distinction raises an uncomfortable possibility: have we been praising serendipity while quietly lowering the bar for what is allowed to count as serendipity?

Have we become too comfortable equating serendipity with surprise — and what have we lost in doing so?

Frankly, we have lost the real lessons learned from the ancient Persian fairytale – the Peregrinaggio of the Three Princes of Serendip.

Follow my essays – or read my book “Serendipity Unleashed – Hidden Wisdom of the Jesters” (forthcoming soon) – to find out the original understanding of Authentic serendipity. Next week I will reveal what role Merton and his “serendipity pattern” have in this mystery.