(Photo courtesy: AI-generated illustration inspired by Theodore G. Remer’s Serendipity and the Three Princes, based on the Peregrinaggio (1557).)

Let us begin with an uncomfortable question.

Is a fictive medieval fairytale really a credible source for serious conclusions about discovery, insight, and organizational intelligence?

At first glance, the answer should be no. A fairytale is not a theory. Not a model. Not evidence.

And yet—apparently—it was enough.

Enough for Horace Walpole, in 1754, to coin an entirely new word: serendipity. Enough for that word to travel centuries, disciplines, and continents. Enough for it to become a fashionable promise—almost a lifestyle expectation—loaded with Hollywood-like dreams of lucky breaks and “happy accidents.”

All this, it seems, based on a sloppy, second-hand, and often careless reading of a story that most people have never actually read—beyond a few early pages, if that.

That alone should make us pause, and perhaps rethink.

The inherited misunderstanding

The dominant modern reading goes something like this:

The Three Princes of Serendip travel and have adventures. They accidentally notice strange clues. They make clever guesses. => Good fortune follows.

Serendipity, in this framing, is:

-

accidental

-

individual

-

retrospective

-

and faintly magical

A charming story. A comforting one. But also a deeply misleading one.

Because when the Peregrinaggio is read carefully—not selectively—something far more interesting, and far more unsettling, emerges.

What the princes actually do

The three princes do not behave like lucky tourists. Not at all. They are on their Peregrinaggio—a pilgrimage—and they are exceptionally well prepared, thanks to their wise father, King Jafer. His understanding of what is required for judgment, rulership, and the long-term stability of an empire forms the silent backbone of the entire narrative.

This is not a story about naïve wandering. It is a story about how the princes acquire wisdom and virtue — how they fulfill their father’s fundamental aim: to become capable rulers.

The fairytale is a remarkably precise lesson in how deliberate preparation and purposeful, collective action lead to success under uncertainty.

The princes observe deliberately. They reason abductively. They cross-validate one another’s interpretations. They are not afraid of speaking the truth. They developed a seasomned strategic mindset. They were curious to learn!

They argue. They refine. They narrate together. They work as a team.

What they demonstrate—often overlooked by modern readers—is the value of authentic teamwork as a cognitive practice, not a management slogan.

This is collective sensemaking at its best.

Enter Emperor Beramo (and why he matters)

The pivotal moment in the story is not a random encounter with a camel-owner in the desert! This matters, because in many Walpolean interpretations of serendipity, random encounters are elevated to a defining, almost magical element of the phenomenon.

In the Peregrinaggio, however, the camel episode is not a moment of discovery, insight, or learning. It is merely a contingent event—important for the unfolding of the story, but not explanatory of the princes’ capabilities. Without it, the princes might never have met Emperor Beramo. That much is true, but contingency is not causality.

The camel did not produce their reasoning. It did not create their collective intelligence. It merely created the occasion in which that intelligence could later be recognized.

The princes are accused. Their reasoning is questioned. Their fate is uncertain. They might face the death penalty.

Then—and only then—luck appears.

The missing camel is found by a neighbor. This single event clears the princes of suspicion and saves their lives.

And this point matters enormously:

It is the only moment in the entire fairytale where luck plays any role at all.

Everything else—the observations, the reasoning, the conclusions, the collective intelligence—was earned.

Luck did not create insight. Luck merely kept insight alive long enough to be heard.

Beramo does not reward the princes because they were right. He rewards them because of how they think, speak, and challenge appearances—together.

What Beramo recognizes is not truth. It is a role. And the impact what princes were able to create.

A role capable of:

-

surfacing inconvenient observations

-

challenging dominant interpretations

-

without threatening the legitimacy of power

In medieval terms, this role was fundamental and had a name. Today, we have almost forgotten it.

The jester was not an entertainer

Modern imagination has reduced the jester to:

-

bells

-

jokes

-

harmless mockery

Often, this mockery is projected onto figures portrayed as mentally or physically impaired—a distortion that tells us more about later European court cultures than about the original function itself.

This is precisely why the term fool is so often used, especially in European traditions.

But the fool and the jester are not the same. The fool is laughed at. The jester is listened to.

The fool entertains power. The jester challenges it—without threatening it.

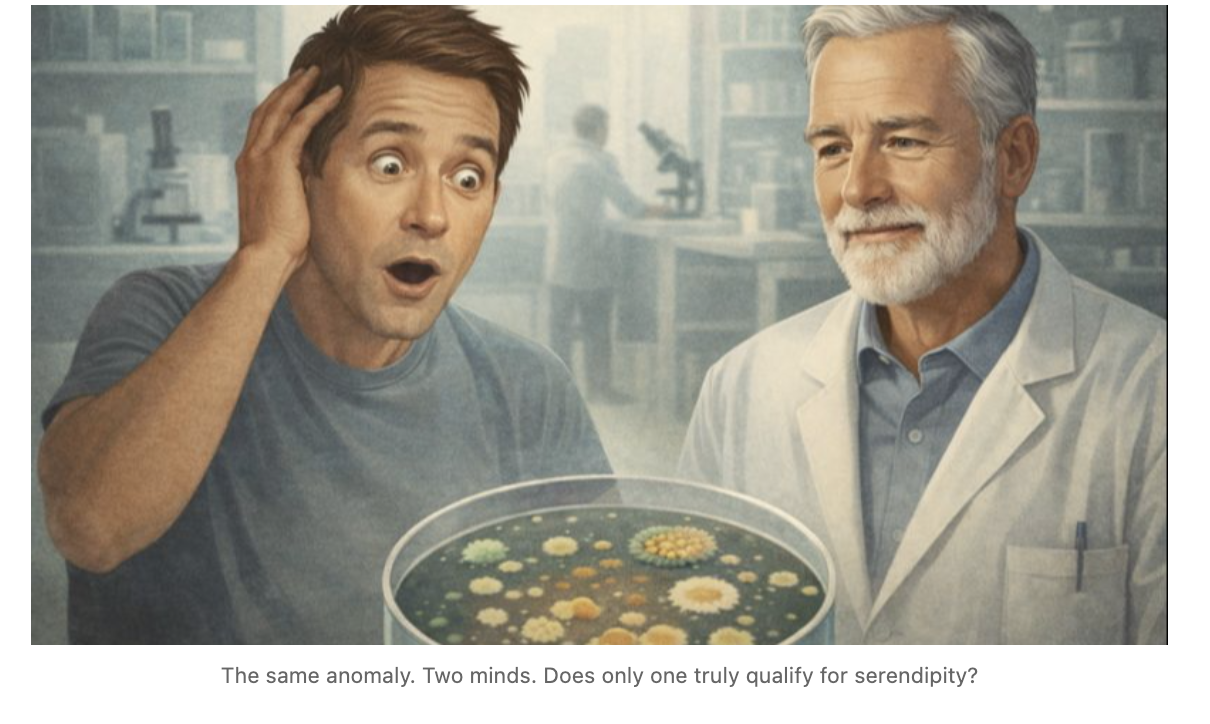

This distinction matters. Because when we collapse the jester into the fool, we also collapse insight into entertainment—and serendipity into spectacle.

Historically, the jester’s function was far more serious.

The jester did not impose truth. He revealed contradictions, enabled bisociation, and redirected attention from the salient to the relevant.

Seen through this lens, the princes do not merely experience serendipity.

They embody it.

A collective practice, not a coincidence

This is where many modern interpretations quietly fail.

Serendipity was never:

-

a solitary flash of brilliance

-

a private “aha” moment

-

or a personal branding story

It was always:

-

relational

-

dialogical

-

and collective

The princes succeed because they think together. They survive because they correct one another.

They are invited into power because they demonstrate disciplined curiosity without arrogance.

That is not an accident. That is a practiced social capability.

Why this reading was lost

So how did we end up with “happy accidents”?

Not because organizations reject serendipity. But because they were offered a misleading version of it.

Modern organizations are not uneasy with observation, anomaly detection, abductive reasoning, storytelling, or implementation. These are already core elements of strategy, innovation, and leadership. What organizations are uneasy with is a popularized narrative that frames serendipity as:

-

starting initiatives in order to “find something you were not looking for”

-

celebrating luck rather than responsibility

-

and detaching discovery from execution and value creation

That version does not survive a single boardroom conversation.

It sounds inspirational—but collapses under accountability. So people in management positions did not reject serendipity.

Business world rejected a bad story about serendipity.

The real distortion

The tragedy is not that modern organizations rejected serendipity. The tragedy is that it was diluted.

A disciplined, collective sensemaking capability was repackaged as a romantic slogan. And when that slogan failed, organizations were blamed for lacking imagination.

Serendipity did not disappear. It was misunderstood—and then misrepresented.

A closing thought

When the slogans are stripped away, something unexpected becomes visible.

Modern organizations already practice much of authentic serendipity—just under different names.

What they lack is not curiosity, insight, or ambition.

What they lack is a recognized role that can:

-

surface contradictions without moralizing

-

enable bisociation without prescribing answers

-

and redirect attention from what is merely salient to what is truly relevant

That role once had a place. We did not outgrow it. We forgot it.

Postscript

To avoid confusion, it is important to distinguish between three different uses of the term serendipity.

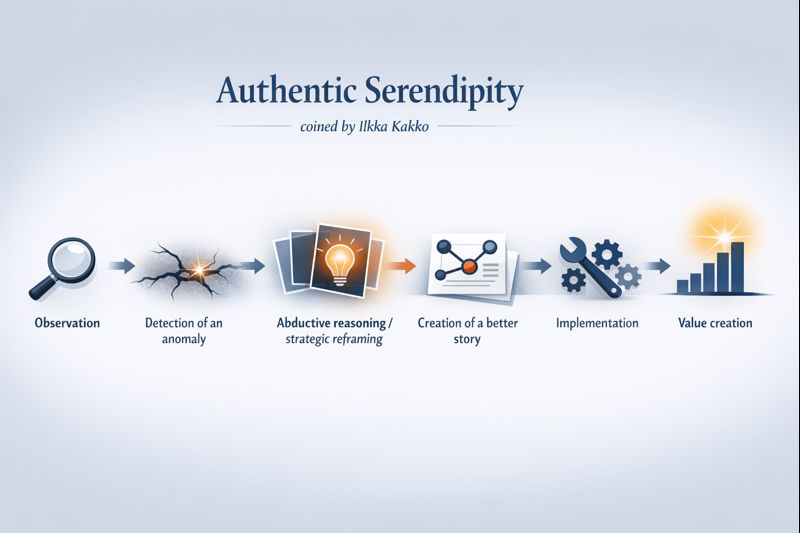

First, serendipity as a phenomenon refers broadly to valuable discoveries that emerge through observation, interpretation, and sensemaking—often in ways not fully planned in advance.

Second, what I will call Walpolean serendipity refers to a specific interpretive tradition originating with Horace Walpole’s famous letter and reinforced by later popular and academic retellings. In this version, serendipity is framed as luck-driven, accidental, unexpected, and defined by finding something valuable while explicitly not looking for it.

Finally, Authentic serendipity refers to what becomes visible when the original Persian fairytale is read carefully rather than symbolically. Here, serendipity appears not as chance, but as a disciplined, collective practice grounded in observation, abductive reasoning, and creating a better story.

And the fundamental insight is this: the three princes were, in effect, exemplary court jesters in Beramo’s court. They validate the role of the jester as a catalyst for authentic serendipity. Serendipity Unleashed.