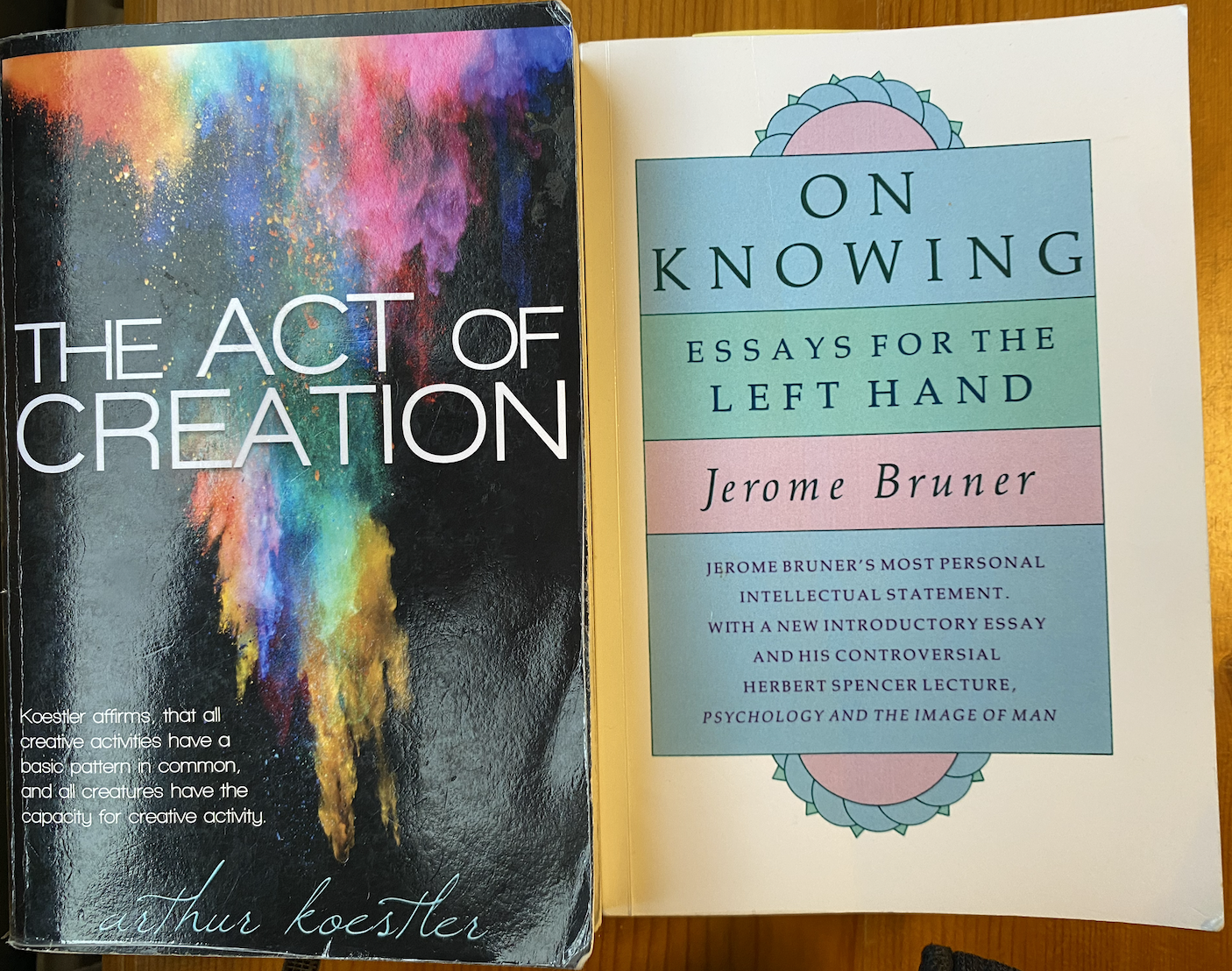

My interest in Koestler’s work is a bit a mystery even to myself. Somehow already years ago, I felt the urge to get the copy of “The Act of Creation” into my bookshelf. Why was that? I have no logical explanation. It was like the blend of magic and mystery. Joseph Jaworski or Daniel Bohm might call it synchronicity. However, to find a copy was a challenging task. At the time when my interest was high (about 2018-19) I was not able to buy it; it was sold out. Then destiny came to my rescue.

My dear friend from South Africa knew about my search and she was able to buy the book there and send it to me. It had this lovely message written on the front cover:

” Dear Ilkka. Each human is an act of creation and a masterpiece. May this masterpiece bring you much joy and fulfilment; may the Jester, Sage and Artist in you enchant and bless the world, and may your creation be recognized and enjoyed by those who are ready to embrace your wisdom and insights. Joyfully, Hannelie”.

I am forever thankful for the Universe for this connection. Therefore, with this book I want to show my gratitude to all who have supported me in this journey.

The Act of Creation is a huge book, both mentally and intellectually and even physically 700+ pages. So, it took a while before I ended up reading it for the first time. Even when first opening of the book and checking the content, Koestler’s archetype classification Jester-Sage-Artist seemed intriguing. What on earth is this Jester and how does it fit to the picture? The more I got to know Koestler’s thinking, the more exited I became of this combo and especially jester’s mythical role in act of creation. My long-term research in serendipity helped me to understand the value what Koestler tried to point out; contradiction was the key and the Jester was the agent to create it!

Arthur Koestler’s decision to include the Jester as one of the three archetypes in his book was a deliberate and intellectually rich choice, grounded in his overarching theory of creativity as bisociation—the intersection of previously unrelated frames of reference. Let’s explore why the Jester became a central figure alongside the Sage and the Artist.

Koestler’s core argument is that creativity through bisociation is the key. He introduces bisociation as the process by which creative acts result from bringing together two unrelated matrices of thought. This mechanism underlies:

- Scientific discovery (Sage)

- Artistic inspiration (Artist)

- Comic insight or humor (Jester)

Each of these creative domains triggers a different emotional response:

- Aesthetic beauty => Artist

- Intellectual understanding => Sage

- Laughter or comic relief => Jester

Koestler thus wasn’t choosing archetypes arbitrarily; he was mapping three key realms of the human experience that rely on bisociation. Koestler argued that humour emerges from the collision of two frames of reference—the classic structure of a joke. This comic collision is cognitively identical to the moments of insight in science and art, but its emotional charge is laughter.

“The pun and the scientific insight spring from the same mental process: the perceiving of a situation or idea in two self-consistent but habitually incompatible frames of reference.”

The Jester, as the master of incongruity, represents this comic form of bisociation. He exposes the absurdities in logic, power, and social norms—not through structured argument, but through playfulness, inversion, and irony.

Koestler was fascinated by how the human mind breaks out of rigid structures. Historically, the court jester was granted license to speak truth to power precisely because he wrapped truth in jest. This made the Jester a socially tolerated deviant, and a catalyst for insight in others. In this way, the Jester isn’t just comic relief but a subversive force who challenges authority, dogma, and common sense—qualities Koestler saw as crucial to creativity.

Koestler aligned the three archetypes with different domains but emphasized they all operate on the same fundamental mechanism of bisociation. Each will challenge habitual thinking, make unexpected connections, and invite new perspectives.

The Jester disrupts logic to make us laugh.

The Sage disrupts logic to explain the world.

The Artist disrupts perception to express meaning.

Koestler’s life, which was marked by political imprisonment, ideological shifts, and deep engagement with both science and art as we described in Chapter 2 made him sensitive to paradox and contradiction. He admired people who could live in ambiguity, were able to subvert norms and had the ability to foster insight through irony. The Jester, therefore, also reflects Koestler’s own intellectual temperament: a skeptic, provocateur, and boundary-crosser.

He admired people who could live in ambiguity, were able to subvert norms and had the ability to foster insight through irony.

I suppose Koestler chose the Jester as one of his three archetypes because humor involves bisociation—just like art and science. The Jester’s incongruous logic reveals hidden truths. He serves as a disrupter of dogma, echoing Koestler’s lifelong fight against rigid ideologies. He embodies a creative attitude of playful rebellion—a quality Koestler believed essential to progress in all fields of thought. The Jester, in Koestler’s hands, is not a fool, but the wisest fool of all—the one who teaches us to laugh at the absurd and through the absurd, to discover what truly matters. Humour is for Koestler not mere entertainment; it’s a cognitive tool that reveals hidden connections and forces us to challenge normed thinking.