Ever wondered how a crazy idea—like landing a rocket like an airplane—becomes reality? Arthur Koestler’s concept of bisociation, from his 1964 book “The Act of Creation”, explains this spark of genius. By colliding two incompatible mental frameworks, or “matrices,” bisociation fuels innovation, as seen in Elon Musk’s reusable rockets at SpaceX. Unlike routine thinking, which operates within a single matrix and relies on old experiences and intuition, bisociation involves a sudden shift or synthesis of contradictory perspectives, resulting in a novel insight.

Unlike routine thinking, which operates within a single matrix and relies on old experiences and intuition, bisociation involves a sudden shift or synthesis of contradictory perspectives, resulting in a novel insight.

Last week, we explored how Musk’s Giga Press, inspired by toy car manufacturing, streamlined Tesla’s chassis production, read here. Now, we turn to SpaceX’s reusable rockets, another triumph of bisociative thinking and Musk’s genius to apply bisociation in practical engineering terms within his innovation activities. The innovation of reusable rocket boosters, pioneered with Falcon 9 and advanced with Starship, fundamentally changed space travel by making rockets recoverable and reusable, slashing launch costs. Let’s identify the two contradictory matrices involved:

-

Traditional Aerospace Matrix: In the early 2000s, when SpaceX was founded, the aerospace industry treated rockets as single-use, expendable vehicles. Rockets, like NASA’s Space Shuttle boosters or earlier Saturn V, were designed to launch payloads into space and then either burn up, crash into the ocean, or be partially salvaged at great cost (e.g., the Shuttle’s solid rocket boosters). This matrix prioritized performance and payload delivery over cost or reusability, viewing rockets as disposable due to the extreme engineering challenges of surviving reentry and landing.

-

Reusable Vehicle Matrix: Everyday transportation systems, like airplanes, cars, or even bicycles, are designed for repeated use. An airplane, for example, takes off, lands, refuels, and flies again with minimal refurbishment. This matrix emphasizes cost-efficiency, repeatability, and sustainability, but it was considered irrelevant to rocketry due to the vastly different physics and economics of space travel.

These matrices are incompatible because rockets face unique challenges: extreme velocities, temperatures, and structural stresses during launch and reentry, which made reusability seem impractical. The prevailing aerospace mindset dismissed reusable rockets as too complex or costly to engineer, with NASA and other agencies favoring expendable systems for decades.

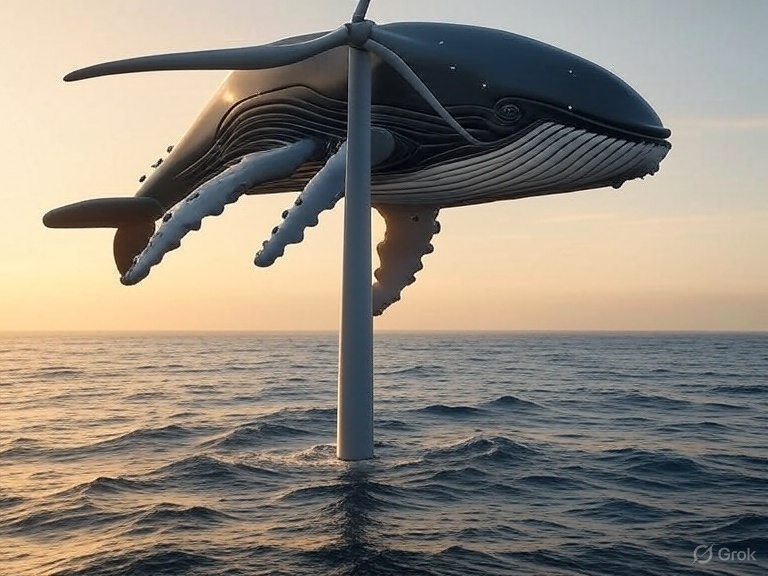

Elon Musk’s bisociative insight was to question why rockets couldn’t operate like airplanes. By synthesizing the reusable vehicle matrix with the aerospace matrix, he envisioned rockets that could launch, return to Earth, land precisely (e.g., on drone ships or launchpads), and fly again after minimal maintenance. This led to SpaceX’s development of Falcon 9’s reusable first-stage boosters and Starship’s fully reusable design, transforming the economics of spaceflight.

While the Giga Press insight had a serendipitous trigger, Musk casually examining a toy car, the reusable rocket concept was more deliberate, driven by Musk’s obsession with making space travel affordable to colonize Mars. However, a touch of serendipity exists in how Musk drew inspiration from unrelated domains. According to Isaacson’s book “Elon Musk”, Musk’s exposure to the airline industry’s reusable model came partly from observing everyday systems, not from aerospace precedent. The “aha” moment wasn’t a single event but a synthesis over time, sparked by Musk’s outsider perspective on the stagnant aerospace industry. His lack of traditional aerospace training allowed him to challenge entrenched assumptions, a hallmark of bisociative thinking.

Musk merged the matrix of traditional aerospace, where rockets were expendable and costs soared, with the matrix of reusable vehicles, like airplanes that fly multiple trips with minimal refurbishment. These domains were worlds apart: rockets endure extreme stresses that seemed to preclude reusability.

The SpaceX’s reusable rocket concept is a clear example of bisociation, as it required Musk to bridge two incompatible domains—aerospace and reusable transportation—defying industry norms. It’s slightly less serendipitous than the Giga Press moment, as it stemmed from Musk’s deliberate goal of cost reduction, but the analogy to airplanes was a creative leap that few in aerospace considered viable. Musk’s genius lies in his determination to find better solutions and his natural tendency for bisociative thinking—whether merging toy manufacturing with cars for the Giga Press or airplane reusability with rockets for SpaceX, he thrives on colliding unrelated domains.

Bisociation isn’t just for Musk and engineers. Try merging unrelated ideas in your own work—whether art, tech or business—to spark your next breakthrough. Share your ideas below!