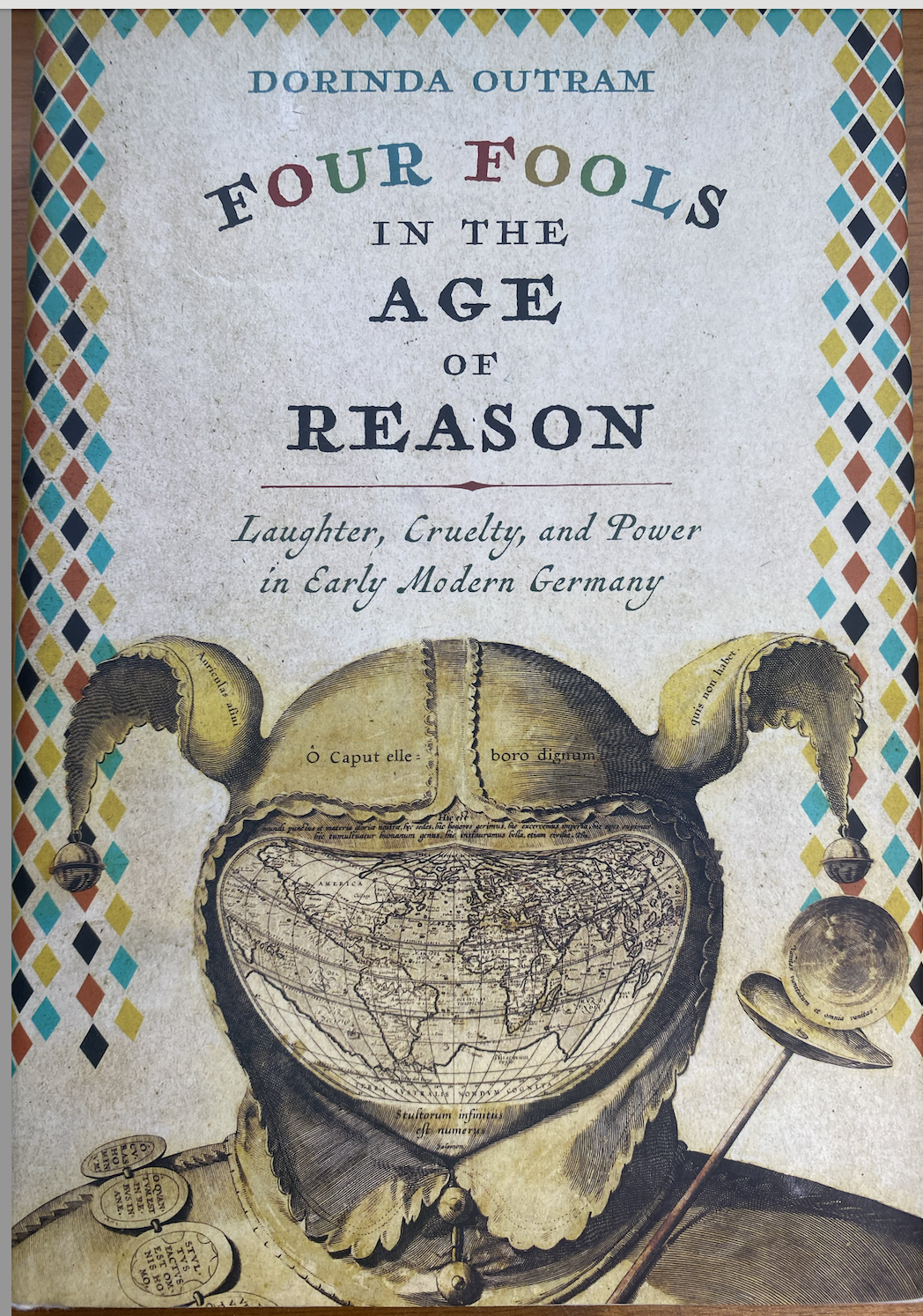

Many books about court jesters resemble catalogues. They present anecdotes, pranks, witty remarks, humiliations, and colorful personalities — valuable material, certainly, but often leaving the reader wondering what all these stories ultimately reveal. Dorinda Outram’s Four Fools in the Age of Reason is different.

Instead of presenting an endless parade of jesters, Outram focuses on four individuals — Jacob Paul Gundling, Salomon Jacob Morgenstern, Joseph Fröhlich, and Peter Prosch — and through them reconstructs the social mechanism in which fooling operated. The result is not merely cultural history but an analysis of power.

Her starting point is deceptively simple: what are we studying when we study fools? Not costumes, nor jokes, nor marginal entertainers — but professionals of contradiction.

Individuals who simultaneously occupied incompatible positions: companions of rulers and objects of ridicule, scholars and buffoons, advisors and victims. Their laughter was visible, but their role was structural. Outram places these figures firmly inside the Enlightenment, a context often imagined as the triumph of reason over irrationality. Her book quietly overturns this assumption. The courts of early modern Germany and Austria did not eliminate irrationality; they institutionalized it. The jester was not a leftover from a medieval past but an active component of an emerging modern order.

The disturbing example of Gundling

One of the most striking figures in the book is Jacob Paul Gundling — a jester with multiple roles: a historian, a president ot the Akademie der Wissenschaften, master of ceremonies,director of silkworm industry and most importantly Zeitungs-Referat (court newspaper reader). His life fits the criteria for a jester/fool established by Karl Friedrich Flögel in his 1789 Geschichte der Hofnarren: the court fool should enetertain; tell the truth; and give good advice; restrain the anger of the monarch; and heal the illness. Only in the last was Gundling deficient.

But in this case he became a sad, human instrument of humiliation. The austere and authoritarian Frederick William I systematically degraded him — fake duels, burning wigs, drunken manipulation, confinement, and even a wine-barrel coffin after death — not merely out of cruelty but as a political method. The message was unmistakable: intellectual prestige would never outrank sovereign authority.

Gundling therefore represents a paradox. He was an Enlightenment scholar, yet the court turned reason itself into an object of ridicule. Laughter was not freedom; it was control. The jester did not challenge power — he demonstrated its limits.

Outram describes fools as embodiments of contradiction — humble and privileged, honored and humiliated, wise and foolish. These contradictions mark the stress points of society: status, legitimacy, and authority.

Laughter, therefore, was not simply entertainment but a tool through which power could be exercised and stabilized. The pleasures of laughter were inseparable from its dangers.

Ridicule as authority

This mechanism does not belong only to early modern courts.

Power has often used ridicule not merely to entertain but to signal hierarchy. Public mockery clarifies who may speak seriously and who may not. The target becomes less important than the spectacle: authority demonstrates itself by defining others as laughable.

Modern politics occasionally employs a remarkably similar dynamic. Leaders do not always refute opponents — they nickname them, imitate them, or reduce them to caricature. The laughter of supporters then performs a function very close to that of the court audience: it binds loyalty and marks boundaries of belonging. What appears spontaneous humor becomes a social sorting mechanism.

Outram’s analysis helps us see that such behavior is not simply personal temperament or rhetorical style. It is a recognizable form of power.

The humiliation of Gundling was extreme, yet the underlying logic — reinforcing authority through staged ridicule — remains surprisingly persistent across centuries.

Why the jester disappeared

Outram’s analysis helps explain why the classical jester later vanished.

Toward the end of the eighteenth century, a new ideal emerged: the rational individual. Society increasingly imagined humans as self-sufficient decision makers guided by logic rather than ritual, hierarchy, or communal interpretation. Courts disappeared, bureaucracies expanded, and ambiguity became suspect. In a world expected to function through calculation, the social role that embodied contradiction lost its place.

The jester did not become unnecessary because society became rational. He became impossible because society believed it was rational.

From individual rationality to social intelligence

Modern research suggests something remarkable: the Enlightenment assumption itself may have been incomplete.

In Social Physics (2014), Alex Pentland demonstrated empirically that intelligence and innovation arise less from isolated cognition than from patterns of interaction — idea flows, turn-taking, diversity, and feedback within networks. What we call good decisions emerge from collective sensemaking rather than individual reasoning.

This brings us unexpectedly close to the historical function Outram describes.

The court jester was not important because he spoke truth. He was important because he reorganized attention. He disrupted fixed interpretations, exposed contradictions, and forced the social system to renegotiate meaning. In modern terms, he altered the dynamics of thinking itself.

Industrial modernity removed the jester because it trusted individual rationality. Network society rediscovers the need for him because cognition is social again.

Why this book matters now

Reading Outram, one gradually realizes that the historical jester was not primarily a truth-teller nor merely an entertainer. He was a tolerated disturbance — a figure allowed to expose contradictions that formal roles could not address. His function was social before it was personal.

If understanding emerges between people rather than inside them, systems again require mechanisms that surface hidden tensions, reframe assumptions, and redirect attention — precisely the function once performed by the jester.

In my forthcoming book Serendipity Unleashed – Hidden Wisdom of the Jesters, I explore this possibility as the idea of the 21st-Century Jester: not a court figure, but a role within communities and organizations that enables collective insight by revealing contradictions and enabling new interpretations.

Outram’s historical analysis does not argue this explicitly — yet it prepares the ground for it. By showing what the jester once stabilized, she helps us recognize what modern systems quietly lack.

In short: This is not merely a book about power, humor and crulety in history. It is a book about how societies manage power — and why they still need someone who can safely disturb it.