1. Why Walpolean Serendipity Fails the Boardroom Test

In most organizations, serendipity is still quietly understood as luck, coincidence, or what is politely called “happy accidents” — a comforting idea, but a disastrous foundation for innovation. Even when mentioned approvingly, it usually signals something that:

-

cannot be planned,

-

cannot be governed,

-

cannot be repeated, and

-

cannot be responsibly funded.

This is not a communication problem.

It is a conceptual failure.

The roots of that failure lie in what I call Walpolean serendipity — the interpretation inherited from Horace Walpole’s 1754 letter, itself based on a highly ambiguous and ultimately misleading reading of the Persian fairytale Peregrinaggio di tre giovani figliuoli del re di Serendippo.

Over time, this reading hardened into defaults that still dominate business discourse today:

-

serendipity as accident,

-

serendipity as individual brilliance,

-

serendipity as retrospective explanation.

The result is predictable. The concept works well in anecdotes, keynote slides, and after-dinner stories — but collapses in environments that must act before outcomes are known.

Even worse, decades of enthusiastic but often undisciplined research have amplified the confusion. Metaphors multiplied. Definitions loosened. Imagination frequently replaced close engagement with original sources. Even the few scholars who openly questioned Walpole’s interpretation — most notably Robert K. Merton and Pek van Andel — have largely been sidelined rather than seriously engaged.

The paradox is striking:

the more serendipity is celebrated, the harder it becomes to apply.

2. Authentic Serendipity — Recalling the Core Distinction

As I argued in the previous Serendipity Unleashed newsletter, this is where a distinction becomes unavoidable.

A careful rereading of The Travels and Adventures of Serendipity and the Persian fairytale Peregrinaggio di tre giovani figliuoli del re di Serendippo by Christoforo Armeno reveals that the anomalies are not in the original narrative, but in how its lessons have been summarized since the eighteenth century. Walpole’s narrow, largely deductive reading of the mule/camel episode simply does not capture the abductive and strategic reasoning that characterizes the princes’ actions throughout the story.

The original narrative tells a far more demanding — and far more useful — story:

how observations are made, anomalies detected, situations reframed abductively, and actions taken to create outcomes of value.

These are not decorative details.

They form a coherent logic.

It was in this context that I introduced the notion of Authentic Serendipity — a framework derived from the internal logic of the Peregrinaggio itself, not from its later misinterpretations.

Authentic serendipity is not a moment of surprise.

It is a disciplined process through which something genuinely new and valuable comes into being.

At its core lies abduction — the only form of reasoning capable of generating new explanatory stories when neither deduction nor induction can help. Remove abduction, and serendipity collapses into coincidence.

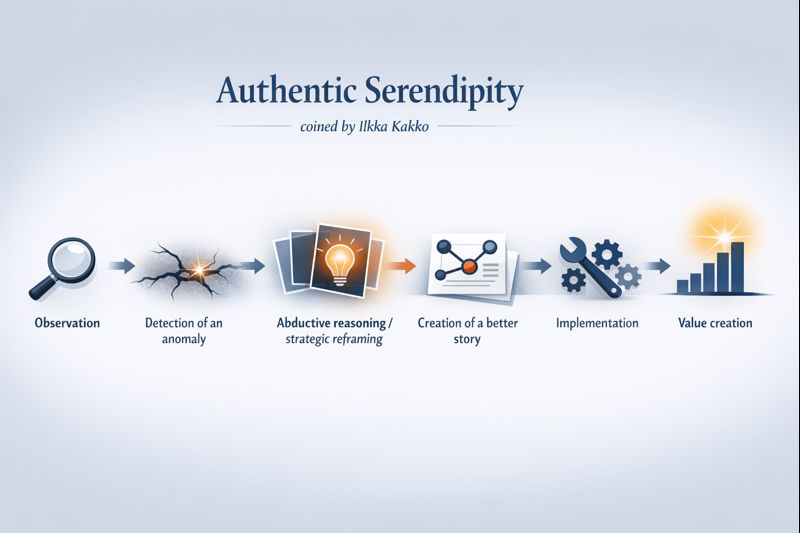

Authentic serendipity unfolds through a demanding chain:

Observation → Detecting an Anomaly → Abductive Reasoning / Strategic Reframing → Creating a Better Story → Implementation → Value Creation

Every link matters.

Insight without implementation may still be interesting — but it is not serendipity.

And perhaps most tellingly: when serendipity is understood this way, words like unexpected, surprise, happy accident, or lucky outcome quietly disappear from the vocabulary. Not because they are forbidden — but because they are no longer needed.

Which also helps ensure we are not escorted out of the boardroom within the first five minutes for proposing “happy accidents” as an innovation strategy. 😉

Walpolean serendipity makes for good stories.

Authentic serendipity survives the boardroom.

3. The 21st-Century Jester: Guardian of the Process

Even when organizations grasp the logic of authentic serendipity, something still tends to break down.

Not because the framework is wrong — but because most organizations are structurally optimized to suppress exactly the behaviors it requires.

This is where the 21st-Century Jester becomes essential.

The Jester is not a decision-maker, not a problem owner, and not a source of ready-made solutions. This distinction is fundamental. The moment the Jester delivers answers, the role collapses into consultancy or Devil’s-Advocate-style provocation.

Instead, the Jester operates as a guardian and catalyst of the serendipity process.

Where the 21st-Century Jester Makes the Difference

Observation

The Jester begins with curiosity and alertness — but observation alone is cheap. Organizations see plenty. The real challenge is noticing what actually matters.

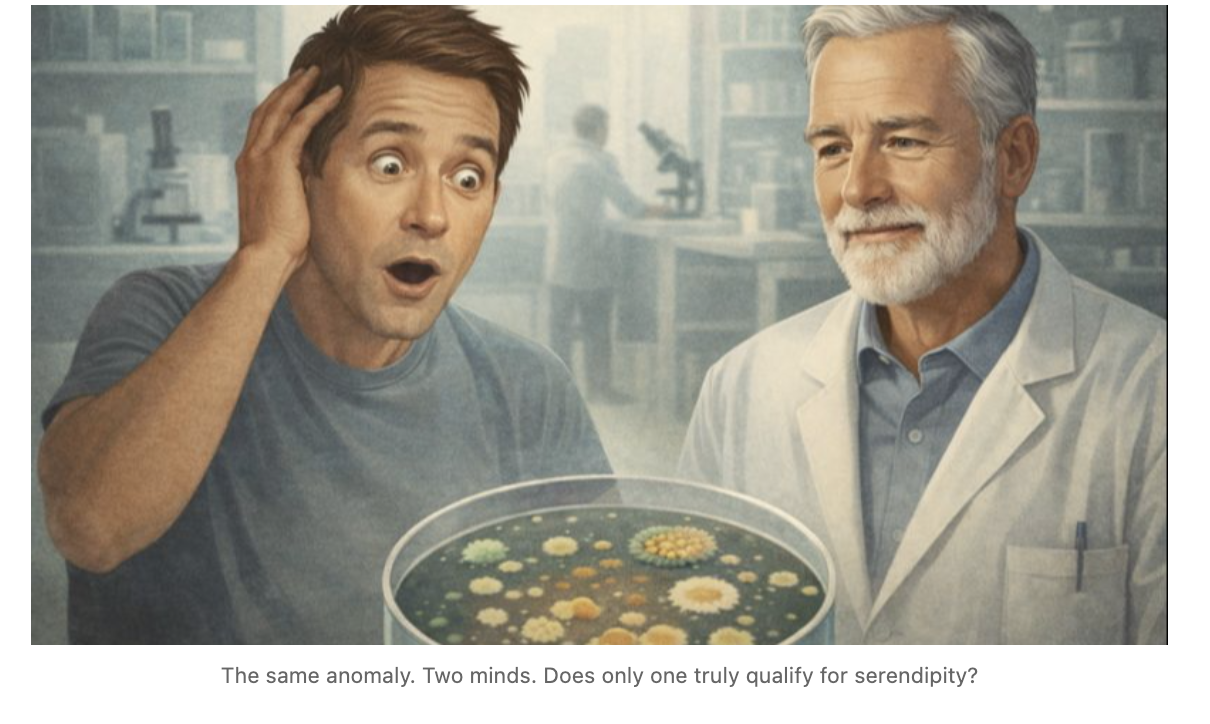

Detecting Anomalies (Bisociation)

Here the Jester’s leverage becomes visible. Anomalies are usually explained away as noise or exceptions. The Jester protects them from premature normalization and is unusually capable of holding incompatible frames at once. This bisociative capacity makes “what doesn’t fit” socially discussable.

Abductive Reasoning / Strategic Reframing

When anomalies surface, organizations instinctively demand proof too early. The Jester legitimizes abductive reasoning — the disciplined leap that asks what could be true here before certainty is available.

Creating a Better Story (Often the Most Impactful Step)

Organizations do not run on facts alone. They run on stories that define what counts as a fact.

The Jester does not impose a new narrative. Instead, he exposes the limits of the existing one and helps others articulate a better story — one that is more coherent, more accurate, more actionable and creates strategic value.

This is often where the Jester’s impact is greatest. Organizations have blind spots — and in my experience, this is the most neglected one of all.

Implementation and Value Creation

Once a better story exists, implementation becomes possible through safe-to-try action. Value is created not only through outcomes, but through strengthened collective sensemaking.

Importantly, ownership always remains inside the organization. The 21st-Century Jester does not create insight for the organization —

he creates the conditions in which the organization can discover it for itself.

NOTE: The Fool/Jester depicted in the cover image is not a character, but a metaphor — a symbolic figure representing a cognitive and social role that enables insight, timing, and sensemaking in the Postnormal Era. He is the guardian of our business peregrinaggio.