Reclaiming Serendipity: From Wild West to Rigorous Pattern

It’s time to write again a serious “Respect Serendipity” essay. The ongoing “Wild West – ambience” in serendipity research needs some counter-argumentation. This essay will introduce a ‘serendipity pattern’, a coinage by Robert K. Merton in the late 1940s and criticize the contemporary state of serendipity research. Merton begun his long engagement with serendipity not as a theorist laying down definitions, but as a scholar recounting a personal, almost incidental moment of encounter

When Serendipity Met a Scholar

“My first consequential encounter with the word ‘serendipity’ was altogether serendipitous,” he writes, recalling how, while searching the Oxford English Dictionary for an entirely different entry, his eye “happened upon the strange-looking and melodious-sounding word serendipity” . The word’s etymology was, as he admits, “far from obvious,” and it was precisely this “etymological obscurity” that made him pause, read more closely, and follow a trail he had not intended to pursue. From the outset, then, serendipity enters Merton’s life not as a romantic idea, but as an unintended detour — a deviation whose significance emerged only afterward.

What struck Merton immediately was not the fairy tale itself, but a defining phrase quoted in the dictionary entry: “discoveries… they were not in quest of.” He notes that this phrase “instantly resonated” with a line of thought already central to his intellectual work — his sustained interest in “the importance of unintended consequences of intended actions in social life.” Long before serendipity became part of his vocabulary, this concern had shaped his doctoral research in the 1930s and was formally articulated in his landmark article “The Unanticipated Consequences of Purposive Social Action,” published in the American Sociological Review, vol. 1 (1936), pp. 894–904.

In this sense, serendipity did not introduce a new fascination for Merton; it named an existing one.

As Merton emphasizes, for its inventor the word signified “a special kind of unintended and unanticipated outcome” — not mere surprise, and certainly not luck, but a patterned relationship between intention, deviation, and meaning.

Seeing the Unanticipated: Serendipity as Pattern

For Merton, serendipity was never about randomness interrupting inquiry, but about how inquiry responds when confronted with the unexpected. He explains that a serendipitous observation is “anomalous, surprising,” precisely because it appears “inconsistent with prevailing theory or with other established facts.” Such inconsistency, he insists, “provokes curiosity” and stimulates the investigator to “make sense of the datum, to fit it into a broader frame of knowledge.”The unexpected is therefore not external to scientific reasoning; it becomes a productive force within it.

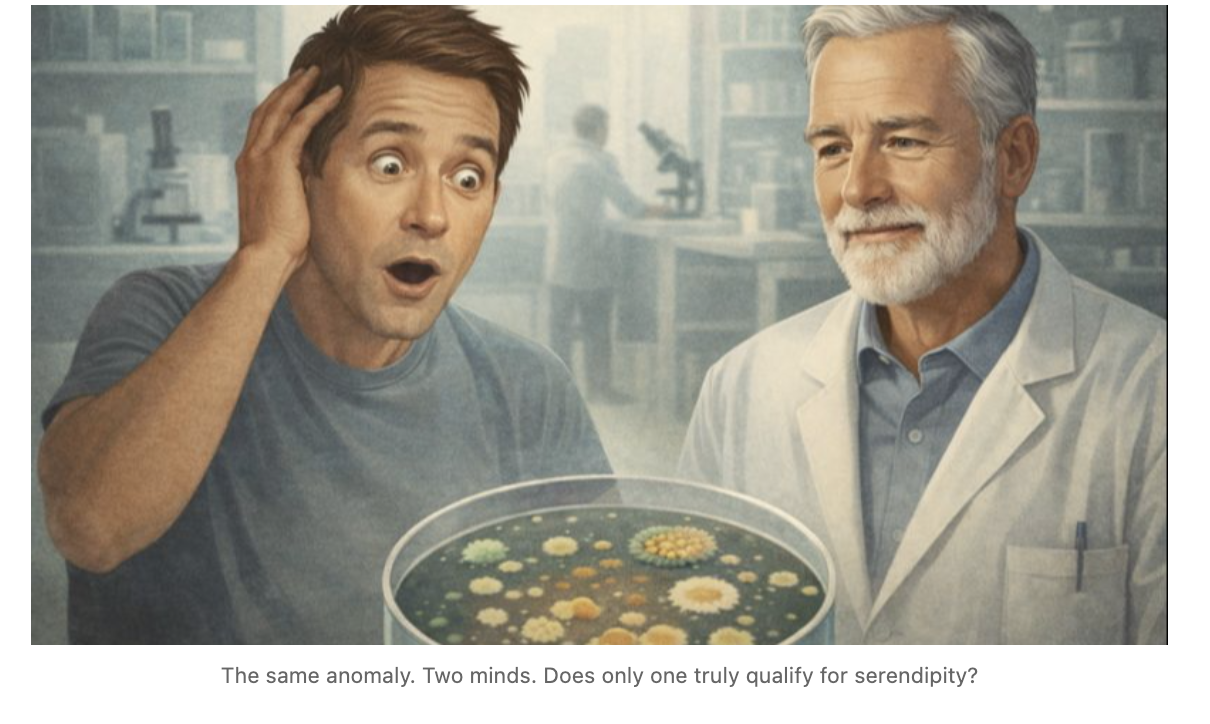

Serendipity, in Merton’s formulation, names a specific moment in inquiry when surprise demands interpretation rather than bypassing it. Crucially, Merton stresses that the pattern involves more than the occurrence of an unexpected fact. “Along with these two components of the unexpected,” he writes, “the serendipity pattern is at least a third component having to do with the scientist who finds the datum evocative.”

The unexpected fact must be strategic — “that it must permit implications which bear upon theory.”

This strategic quality does not reside in the datum alone, but in the observer’s capacity to recognize its significance.

As Merton puts it, this requires “a theoretically sensitized observer to detect the universal in the particular.” The unanticipated, anomalous, and strategic datum is therefore “not simply ‘out there,’ but is in part (but only in part) a cognitive ‘construction,’” shaped by the observer’s theoretical orientation and knowledge, both explicit and tacit. In short, serendipity is not blind luck, but a disciplined interaction between unanticipated observation and interpretive responsibility — one capable of “developing a new theory or extending an existing one.”

The Discipline Behind the Pattern

Merton’s authority in this discussion rests not only on conceptual clarity, but on an intellectual legacy defined by rigor, patience, and extraordinary scholarly discipline.

He was not a casual theorist of discovery, but one of the most exacting sociologists of the twentieth century—the same mind that produced On the Shoulders of Giants, a work that exemplifies his method: meticulous historical excavation, careful attribution, and a deep respect for the cumulative nature of knowledge.

It is therefore telling that his book explaining the early dissemination of serendipity – until mid 1950s The Travels and Adventures of Serendipity was substantially completed as a manuscript already in 1957, and yet deliberately left unpublished—time-capsuled for more than forty-five years. This was not neglect, nor indecision, but a conscious act by a scholar acutely aware of how ideas travel, mutate, and lose precision once released into the world. Why Merton chose to withhold this work for so long is a question rarely asked—and one I will address directly in my forthcoming book.

The Serendipitous Error

Ironically, the word serendipity is itself a serendipitous error — not because it is misleading, but because it sneaked into our vocabulary without the very discipline the phenomenon itself requires. Merton’s serendipity pattern was an attempt to impose rigor where looseness would otherwise prevail. Yet much contemporary discourse celebrates serendipity while quietly stripping away its strategic core: retaining surprise, but abandoning interpretation and abduction; praising chance, while neglecting responsibility.

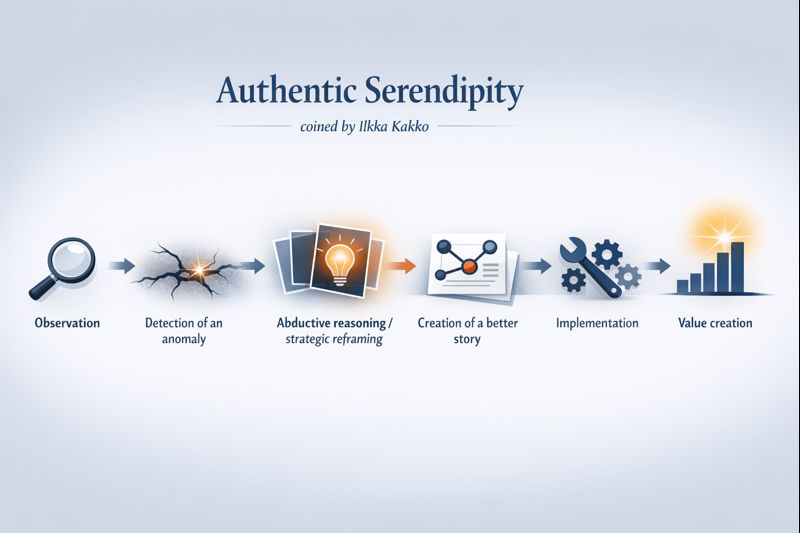

Authentic Serendipity: From Anomaly to Value

Building on Merton’s pattern, I have started to use the term Authentic Serendipity to describe what happens after an anomaly is noticed — when interpretation does not stop at the unanticipated, but continues deliberately toward consequence. In its simplest form, the process unfolds as: observation → detecting anomalies → abductive reasoning and strategic thinking → creating a better theory or story → implementation → value creation. As Gary Klein has shown, insight is not merely a moment of recognition but “an unexpected shift to a better story.” (Here and elsewhere I use unanticipated in Merton’s technical sense — not simply “unexpected”.)

Why Walpolean Serendipity Fails in the Boardroom

This distinction becomes critical when we attempt to bring serendipitous thinking into boardroom-level decision-making. What is often labeled today as “Walpolean serendipity” — still the mainstream interpretation — has never been convincing in a business context. Consider how such a pitch would sound in a strategy meeting:

“I suggest we start a project where we aim to find X, but then (hopefully) discover Y — something we were not in quest of. Let’s allocate five million to this exploratory initiative.”

Not a Feeling — A Structured Process

Serendipity was never about a feeling. Merton’s examples illustrate clearly that, even in his thinking, serendipity began as an observation of a phenomenon and gradually took shape as a pattern. In business contexts, this often means creating a better story — one that can be tested, implemented, and turned into value.

Serendipity becomes dangerous in organizations when it’s not respected — when it is taken lightly.

Lessons Learned from the Persian Fairytale’s Legacy

Authentic serendipity insists that the story must then be tested, enacted, and translated into real-world value. This logic is not new. Authentic serendipity reflects the deeper lessons embedded in the original Persian fairytale of the Peregrinaggio of the Princes of Serendip — a narrative of observation, abductive reasoning, strategic thinking, collective sensemaking, and purposeful intervention. Those lessons, largely missed in later retellings, point to serendipity not as accidental discovery, but as a disciplined journey from anomaly to value.

In my next essay, I will unpack my Peregrinaggio in detail — and explain what the Princes themselves understood about serendipity, but what we collectively lost when the concept was defined through a sloppy and indifferent reading of the tale, whose title alone inspired Walpole’s coinage, not the hard-won wisdom embedded in Persian fairytale ‘s legacy.

Wishing you a thoughtful New Year! May Kairos be with you —keeping you attentive to the moments that matter, and ready to recognize the opportunities worth grasping.

(the italics are the quotes of Merton&Barber: The Travels and Adventures of Serendipity, 2004)