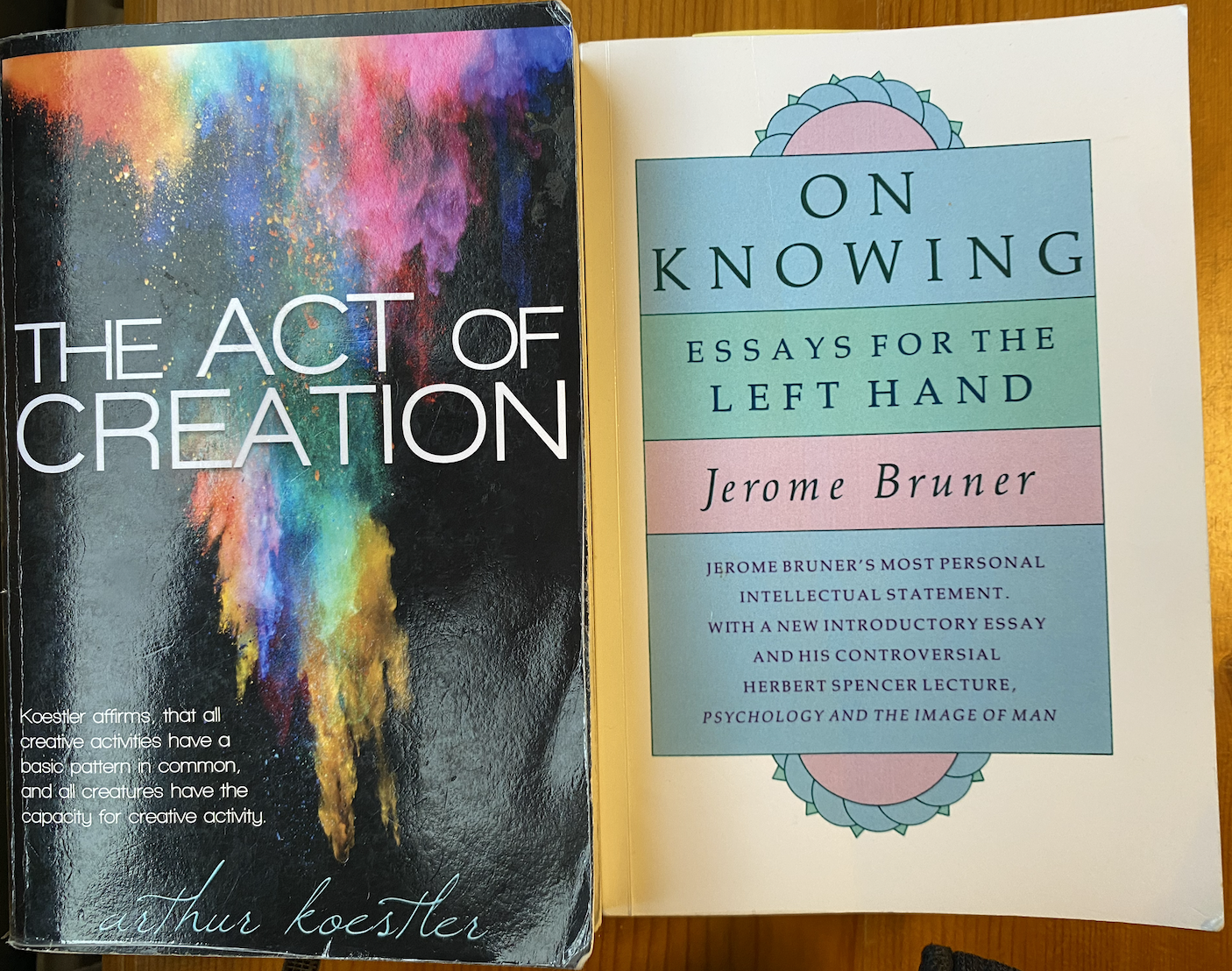

In 1962, American cognitive psychologist Jerome Bruner published a quiet but luminous essay titled The Act of Discovery. Just 20 pages long, tucked into his collection On Knowing: Essays for the Left Hand, it carried the force of a philosophical depth charge. Two years later, in 1964, Hungarian-British journalist, foreign correspondent, and cosmopolitan author Arthur Koestler released his magnum opus The Act of Creation — a sweeping 700-page exploration of creativity, humor, and insight, introducing the now-classic concept of bisociation.

The titles? Nearly identical.

The themes? Uncannily aligned.

The citations? Bruner is never mentioned!

A mere oversight? A disciplinary blind spot? Or a textbook case of the ripe-fruit phenomenon — when the intellectual climate makes certain discoveries not just possible, but almost inevitable? It’s the same cognitive coincidence that gave us Darwin and Wallace, Newton and Leibniz, or Fleming and Florey. And perhaps now: Bruner and Koestler — two thinkers tracing different paths to the same insight:

Discovery is not a step-by-step procedure — it’s a surprise born from the rearrangement of meaning.

Bruner’s invisible influence is his insight that discovery and argument is a surprise! Bruner’s core idea is deceptively simple: “An act that produces effective surprise — this I shall take as the hallmark of a creative enterprise.“ Discovery, he argues, is not achieved through methodical plodding but through restructuring — seeing what we already know in a new frame. It’s close to wisdom by Albert Szent-Györgyi, the Hungarian physiologist who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1937 for his discovery of vitamin C and the components of the citric acid cycle. His famous wisdom “Discovery consists of seeing what everybody has seen and thinking what nobody has thought” has been for me a clever way of explaining the differences between Walpolean serendipity and Authentic serendipity, I introduce these new terms in my forthcoming book Serendipity Unleashed – Hidden Wisdom of the Jesters.

Bruner defines three types of “effectiveness” in surprise:

-

Predictive: insight that leads to powerful generalizations.

-

Formal: internal harmony, elegance, or logic.

-

Metaphoric: the unexpected joining of dissimilar domains.

Jerome Bruner speaks of the shock of recognition — that uncanny moment when something unfamiliar suddenly feels deeply right. If you’ve read Gary Klein, this resonates with his insight as a shift to a better story and his brilliant coinage creative desperation, which is one cornerstone in my authentic serendipity framework. If you’re familiar with the work of Koestler, you’ll recognize this is bisociation in action. If you favor Robert K. Merton’s take on serendipity, Bruner offers the cognitive blueprint for Walpole’s questionable coinage of accidental sagacity. And as Pek van Andel later emphasized, serendipity is not about luck or ‘serendipitous encounters’ — it’s about recognizing the significance of the unexpected, spotting anomalies and trusting in abduction*. Bruner, without using the term, is actually describing the psychological conditions of authentic serendipity!

Spacious Mode Before It Had a Name

Bruner anticipated this already sixty years ago! In On Knowing, he introduced the metaphor of the “left hand” — the awkward, intuitive, mythic mode of cognition:“It is the awkward hand, the illegitimate, the one that stirs hunches and metaphors. But it is the hand that carries the great hypotheses of science.“

Where Reitz and Higgins call for more space to think, Bruner demanded freedom to go beyond the information given, the license to create a better story! His vision wasn’t slow productivity — it was creative re-seeing, built on play, ambiguity, and insight. Bruner also warned us about “banality trap”: “The road to banality is paved with creative intentions.”

This is Bruner at his most jesterish. A brilliant twist on the old proverb “The road to hell is paved with good intentions.” Here, he skewers the performative chase for originality — the kind that produces not novelty, but cliché.

He’s saying that merely intending to be creative — or claiming creativity as your goal — is not enough. It often leads to the most predictable, derivative, uninspired outcomes possible.

“Bruner’s Banality, Zemblanity and the Satire Trap”

This Brunerian warning connects beautifully with a hilarious concept from novelist William Boyd: zemblanity — coined as a jesterish bait for those who love to fall into satire-trap; it’s my new coinage for a funny, yet embarrassing, situation where jesterish wit is taken seriously — even by experts! Where serendipity is the the art of making unexpected discovery of something valuable while looking for something else; zemblanity is the deliberate or inevitable discovery of unfortunate outcomes through systematic, habitual, or misguided actions. What a great way Boyd found in mocking people carried away by Walpole’s sloppy reading of the old Persian fairytale!

Boyd named his coinage after Novaya Zemlya, a barren Arctic island used for Russian nuclear testing — the symbolic inverse of Serendip (modern-day Sri Lanka), the lush island where The Three Princes of Serendip, from the Peregrinaggio of 1557 by Remer started their historical pilgrimage to mainland India and Persia.

So when your pursuit of “creativity” leads to reheated slogans and derivative TED talks? That’s not creativity, even less serendipity. That’s what Boyd jokingly called zemblanity. And Bruner saw it coming.

The silence around Bruner in Koestler’s 1964 work invites us to revisit the idea of Merton’s classic: On the Shoulders of Giants (OTSOG). What if Bruner was one of those unnamed shoulders for Koestler? Not the loudest voice, but the one quietly stabilizing the scaffold of his insight? While Koestler dazzled with cosmic metaphors and literary flair, Bruner gave us the precise, psychological conditions for discovery. This isn’t to discredit Koestler. It’s to respect the chorus of minds who arrive, independently, at the same conceptual frontier. We may just say in our jesterish way: True insight echoes — not from imitation, but from readiness.

Bruner was never just a psychologist. He was a cognitive cartographer of the left-hand path — mapping the mythic, metaphorical, antic spaces where discovery lives. That his ideas are resurfacing today, often uncredited or renamed, is not a tragedy. It’s a victory.

Because in the long arc of understanding, the Jester always returns. And the moment is now.

Before we celebrate The Act of Creation, let us remember The Act of Discovery.

And as we reach for novelty, let us never forget:

“The road to banality is paved with creative intentions.” (Bruner)

Let’s tread lightly. Don’t charge forward with loud, performative creativity. Be aware that even good intentions can lead to zemblanity. Respect nuance. Honor forgotten insights. Stay jesterish.

And smile in mind!

“You have to be very careful if you don’t know where you are going, because you might not get there.” (Yogi Berra)

* Detecting anomalies and trusting in abduction—that’s the essence of Bruner’s “shock of recognition.” Abduction, as pioneered by Charles Sanders Peirce, is the logical leap from puzzling observations to the best explanatory hypothesis, blending intuition and inference to form a “better story.” In my framework of Authentic serendipity, this fits seamlessly into the process: Observation => Detecting anomalies => Abductive reasoning => New hypothesis/a better story => Strategic action => Value creation.

Serendipitor

I used to call myself an explorer of life — but over time I’ve realized that my journey is not about exploration. It’s been a series of Peregrinaggios — pilgrimages of the mind and heart. Life is far too sacred to be wandered through as a tourist. Better to travel it as a pilgrim, open to what unfolds, humbled by what reveals itself along the way.

Read more